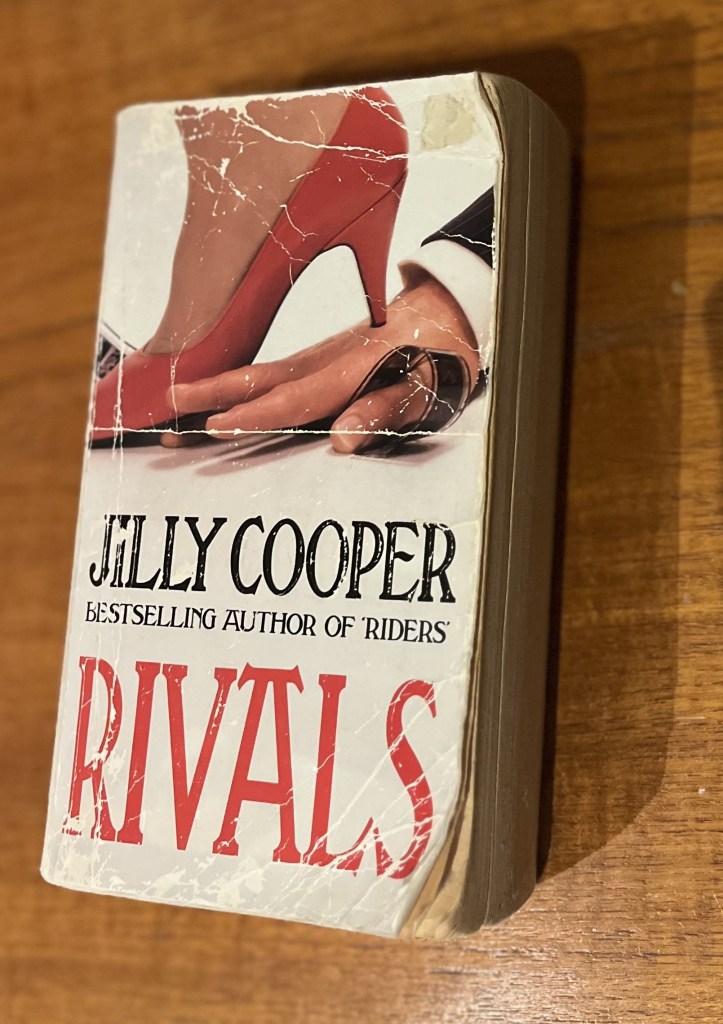

Everybody’s talking about the joy of Rivals, the new Disney+/ Hulu adaptation of Jilly Cooper’s 1986 novel. Commonly described as a ‘bonkbuster’ (posh 80s lingo, darling), the tv adaptation mixes 80’s nostalgia with the thrill of hedonism and a side of ‘how the other half live’ along with a breath-takingly stellar cast. It’s a stonker. It’s also manna from heaven for culture writers who have variously described the show as ‘deeply serious about pleasure’, using watches to see into the characters’ motivations, and being so notable for telling us about life before dating apps.

I’m as big a Jilly Cooper fan as any, ever since I discovered her first book Riders on a bookcase in our holiday gite in Normandy age 14 (much to the dismay of my mother). But I’ve often felt a little embarrassed to admit I’ve read all her books. And while my mother was one of many who once looked down on Jilly Cooper’s writing, now it’s cool – chic, even – to appreciate the show.

The question of what is ‘good culture’ has been around for centuries – ever since Joshua Reynolds as Master of the Royal Academy ruled supreme in a world where only art depicting biblical battles (and at a stretch the odd Greek myth – the bloodier the better) could be hung on its walls. But plucky Hogarth didn’t care a jot, and he pressed ahead with his beautiful portrait of the lowly little shrimp girl and his socially searching and often disgusting satires Marriage a la Mode and the Rake’s Progress. Now these paintings can be seen in the National Gallery because ‘high art’ and ‘low art’ have an annoying habit of blurring their boundaries, and sometimes it’s hard to keep track of what is high and what is low. And it takes a masters in art itself – or maybe in reading Tatler – to know what is currently good taste and what is not.

But appreciating culture for what it says about society and actually enjoying it are two different things – remember Vivian crying in the opera in Pretty Women or Eliza Dolittle screaming at the horses in My Fair Lady? In their unconditioned wonder of opera and horseracing, they showed that it’s fine to love something just for the thrill of it. That is why it is important that kids learn to play the violin in Year 3, that they learn about the Greek gods, or visit a gallery and sketch a painting. And why they also need to go to laser quest, ride the flumes at the water park and be a pinball wizard on Brighton pier. Art and culture is a means of expression but it primarily exists to make our lives more enjoyable and to bring us pleasure.

The main reason why my love for Jilly Cooper is so enduring is because it offers first class escapism: I can turn my brain off and enjoy it for the hell of it. To make it worthy or a searing critique about society would be to lose all its joy. Everyone acting in Rivals looks like they’re having a blast. I’m having a blast watching it. And that is why the show has been so brilliantly successful.

November 2024